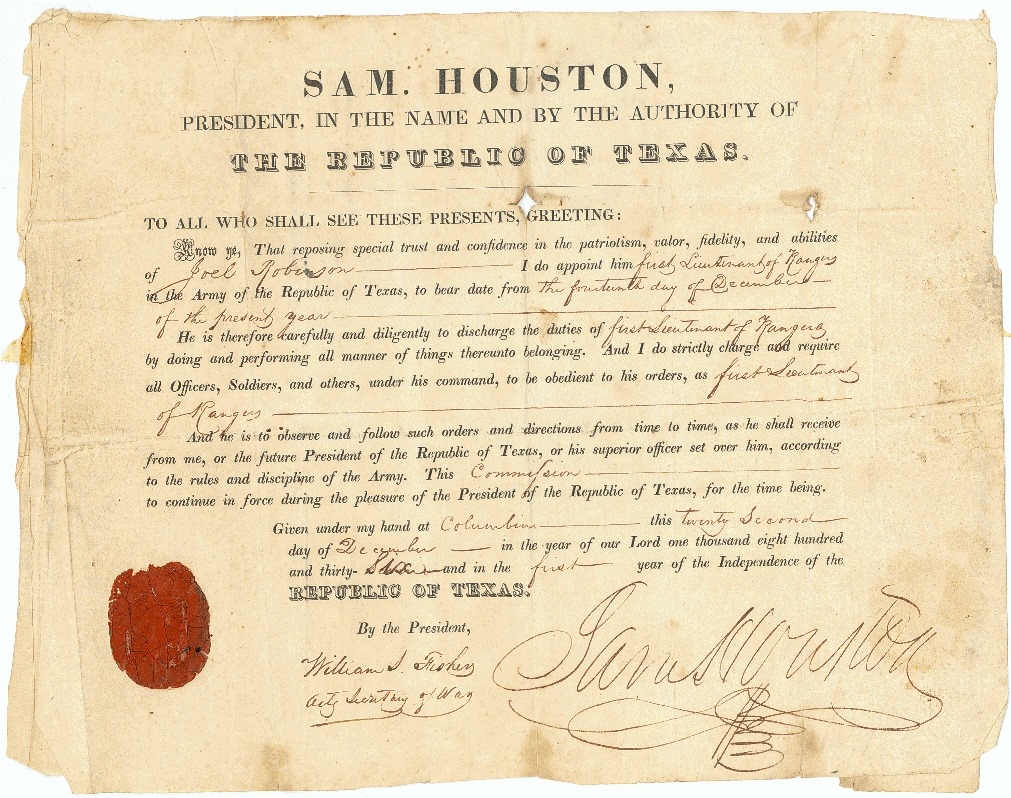

Our friends at the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame & Museum have shared a fascinating document from 1836, Texas’ first year as a Republic, wherein Brother Sam Houston commissioned fellow Mason Joel Robison as a Texas Ranger. You can see more about it on their website here: https://www.texasranger.org/texas-ranger-museum/museum-collections/other-artifacts/commission/

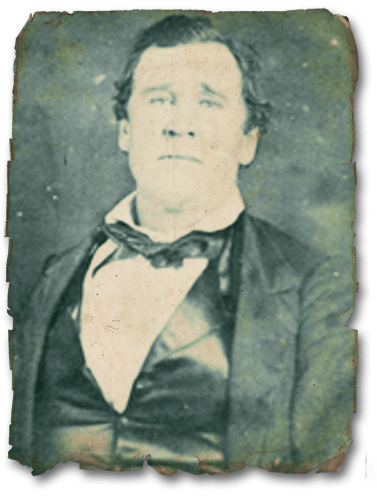

Houston’s heroic status in the annals of Texas history is well established but sadly, Past Master Robison has been mostly forgotten by even the proudest of Texans.

In 1831 and at the age of 16, Joel Walter Robison moved with his family from Georgia to the village of Velasco(part of Freeport today). When the time came for the settlers of Texas to revolt and claim her lands as independent, Robison readily answered the call. He participated in key skirmishes and then really made his mark on Texas history after the deciding victory at San Jacinto. In his own words:

“I was one of a detachment of thirty or forty men commanded by Colonel Burleson, which left the encampment of the Texas army at sunrise of the morning after the Battle of San Jacinto, to pursue the fugitive enemy. Most of us were mounted on horses captured from the Mexicans. We… proceeded a short distance farther down the bayou, but not finding any Mexicans, turned our course toward camp. About two miles east of Vince’s Bayou, the road leading from the bridge to the battleground crossed a ravine a short distance below its source. As we approached this ravine we discovered a man standing in the prairie near one of the groves. He was dressed in citizen’s clothing, a blue cottonade frock coat and pantaloons. I was the only one of our party who spoke any Spanish. I asked the prisoner various questions, which he answered readily. In reply to the question whether he knew where Santa Anna and Cos were, he said he presumed they had gone to the Brazos. He said he was not aware that there were any of his countrymen concealed near him, but said there might be in the thicket along the ravine. Miles mounted the prisoner on his horse and walked as far as the road, about a mile. Here he ordered the prisoner to dismount, which he did with great reluctance. He walked slowly and apparently with pain. Miles, who was a rough, reckless fellow, was carrying a Mexican lance, which he had picked up during the morning. With this weapon he occasionally slightly pricked the prisoner to quicken his pace, which sometimes amounted to a trot. At length he stopped and begged permission to ride saying that he belonged to the cavalry and was unaccustomed to walking. We paused and deliberated as to what should be done with him. I asked him if he would go on to our army if left to travel at his leisure. He replied that he would. Miles insisted that the prisoner should be left behind, but said that if he were left, he would kill him. At length my compassion for the prisoner moved me to mount him behind me. I also took charge of his bundle. He was disposed to converse as we rode along; asked me many questions, the first of which was, ‘Did General Houston command in person in the action of yesterday?’ He also asked how many prisoners we had taken and what we were going to do with them. When, in answer to an inquiry, I informed him that the Texian force in the battle of the preceding day was less than eight hundred men, he said I was surely mistaken, that our force was certainly much greater. In turn, I plied the prisoner with divers questions. I remember asking him why he came to Texas to fight against us, to which he replied that he was a private soldier, and was bound to obey his officers. I asked him if he had a family. He replied in the affirmative, but when I inquired, ‘Do you expect to see them again?’ his only answer was a shrug of the shoulders. We rode to that part of our camp where the prisoners were kept, in order to deliver our trooper to the guard. What was our astonishment, as we approached the guard, to hear the prisoners exclaiming, ‘El Presidente! El Presidente!’ by which we were made aware that we had unwittingly captured the ‘Napoleon of the West.’ The news spread almost instantaneously through our camp, and we had scarcely dismounted ere we were surrounded by an excited crowd. Some of our officers immediately took charge of the illustrious captive and conducted him to the tent of General Houston.”

And so it was that Brother Robison led the capture of fellow Mason Santa Anna, effectively winning Texas her independence. The sword he carried that day(picture three) is on display at the Bryan Museum in Galveston. After the War, he served in various political and social capacities throughout an honorable life. He also spent one year as the Master of Florida Masonic Lodge No. 46 in the town of Round Top. By the time he passed away in 1889, he was one of the last remaining Texas Revolution veterans and beloved by all as a hero of a past generation.